#VijanaNdioMpango: Youth are the Future

This week August 1-10, 2021, Imara Tech is launching the #VijanaNdioMpango campaign, a social media campaign to discuss challenges and opportunities for youth employment. Over the next week, we will be sharing stories, pictures, videos, and ideas about building an economy that is inclusive of our generation and the next. Follow along with our campaign by joining our mailing list, following our LinkedIn page, or checking our website.

This campaign has been generously supported by Soybean Innovation Lab.

Day 1: Campaign Overview

Tanzania has 44M people under 35, 25M of them who are under 15 (National Bureau of Statistics 2021). In an editorial from June 17, Tanzania's largest English newspaper The Citizen wrote:

“Youth unemployment is a ticking time bomb waiting to explode. But, if there is a functional strategy in place which enables them to earn a living and contribute to the economy, then peace and harmony would prevail in our communities.”

What jobs will all of these young people work? What is the future of work in Tanzania?

This week, join us as we discuss the challenges and opportunities for better youth employment through our #VijanaNdioMpango campaign.

Day 2: Challenges of Youth Unemployment

Photo Credit: The Citizen, “Tanzania: Why youth unemployment is still ‘the elephant in the room...’”, October 24, 2020

Tanzania is a country of young people. Over half of the country is below the age of 20 and 77% are below 35 (1).

What jobs will all of these young people work? What is the future of work in Tanzania?

Finding a job is never easy but the cards seem stacked against many of Tanzania’s youth, the majority of which come from rural areas. Two thirds of the workforce in Tanzanian have livelihoods in agriculture (2) and yet the majority of farms remain reliant on unproductive manual farming methods (3). Across the country, young people are leaving rural areas in search of better opportunities than to farm by hand (4) and farming will not be the livelihood of the future if it remains outdated and inefficient.

Youth, especially rural youth, find it difficult to compete in over-saturated urban job markets (5). Informal employment in urban areas, such as street vending or petty trading, employs more than 75% of total non-agricultural workers (6), 70% of young women, and 60% of young men (7). While the informal economy is understood to play an important role as an employer and service provider (8), it has shortcomings. Informal economy earnings tend to be extremely low (9) and the increasing number of street vendors and petty traders is causing tension in the public sphere (10).

The consequences of large-scale unemployment are expected to be severe. At the least, the Ministry of Labour in Tanzania has described the issue as a “tragic waste of human potential” and that it may “increase social and economic burdens” and “psychological frustration” (5).

At its worst, youth unemployment may be a major contributor to instability in the coming decades. One study of Boko Harem’s recruitment of youth in northern Nigeria identified that youth unemployment and poverty are the second most important reason why youth engage in religious-based violence (11). In Ethiopia, a BBC report shows the dangerous journeys that young migrants undertook in search of well-paying employment (all this taking place prior to the present-day conflict in Tigray) (12).

With time, youth employment issues continue to grow, with estimates that out of the 700,000 – 1 million youth entering the labor market each year in Tanzania, only 50,000 – 80,000 get jobs (13). What can be done to address this before the "ticking time bomb" explodes?

Sources

National Bureau of Statistics, 2021

World Bank Employment in Agriculture (Modeled ILO Estimate)

FAO Smallholder Data Portrait

Duda et al, Drivers of rural-urban migration and impact on food security in rural Tanzania, 2019

Ministry of Labour, Employment, and Youth Development, National Youth Employment Action Plan, 2007

ILO, Statistical update on employment in the informal economy, 2012

UN Habitat, 2007

Juma, The role of petty trade on the growth of youth employment at ilala municipality in Dar-es-salaam, Tanzania, 2014

Steiler and Nyirenda, Towards sustainable livelihoods in the Tanzanian informal economy, 2021

Kalumbia, “Why the petty traders issue can’t be ignored”, The Citizen, June 18, 2021.

Onuoha, Why do youth join Boko Harem?, 2014.

“Ethiopian migrants face robbery, extortion and starvation”, BBC Africa Eye, 2021,

https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-africa-57447744.Kalumbia, “Tanzania must change ways of empowering the youth: call”, The Citizen, June 13, 2021.

Day 3: Creating Opportunities for Youth Employment

Agriculture is the single biggest employer in Tanzania. But so often, it’s not perceived as a “real” job. Although subsistence agriculture is in decline, subsistence farming still represented 31% of farms in 2014, with small farms broadly accounting for 88% of all farms and providing livelihoods for 91% of rural households (1).

Agricultural productivity and incomes on small farms are presently low, but improving the productivity of small farms is a huge opportunity for economic development and employment. Mechanizing millions of small farms in Tanzania means not only improving the livelihoods of the farm owners, but also creating thousands of jobs delivering mechanized services to smallholders.

Can mechanization and agriculture really be a sustainable livelihood for millions? YES!

Mechanization can increase yields per acre while also increasing the amount of land a single farmer can manage, boosting farmer incomes and creating jobs in service provision. Technology can also be a means for promoting sustainable agriculture by integrating sustainable practices (e.g. cover crop planting) into a service that farmers are willing to pay for in the short term (e.g. mechanized, no-fuss planting).

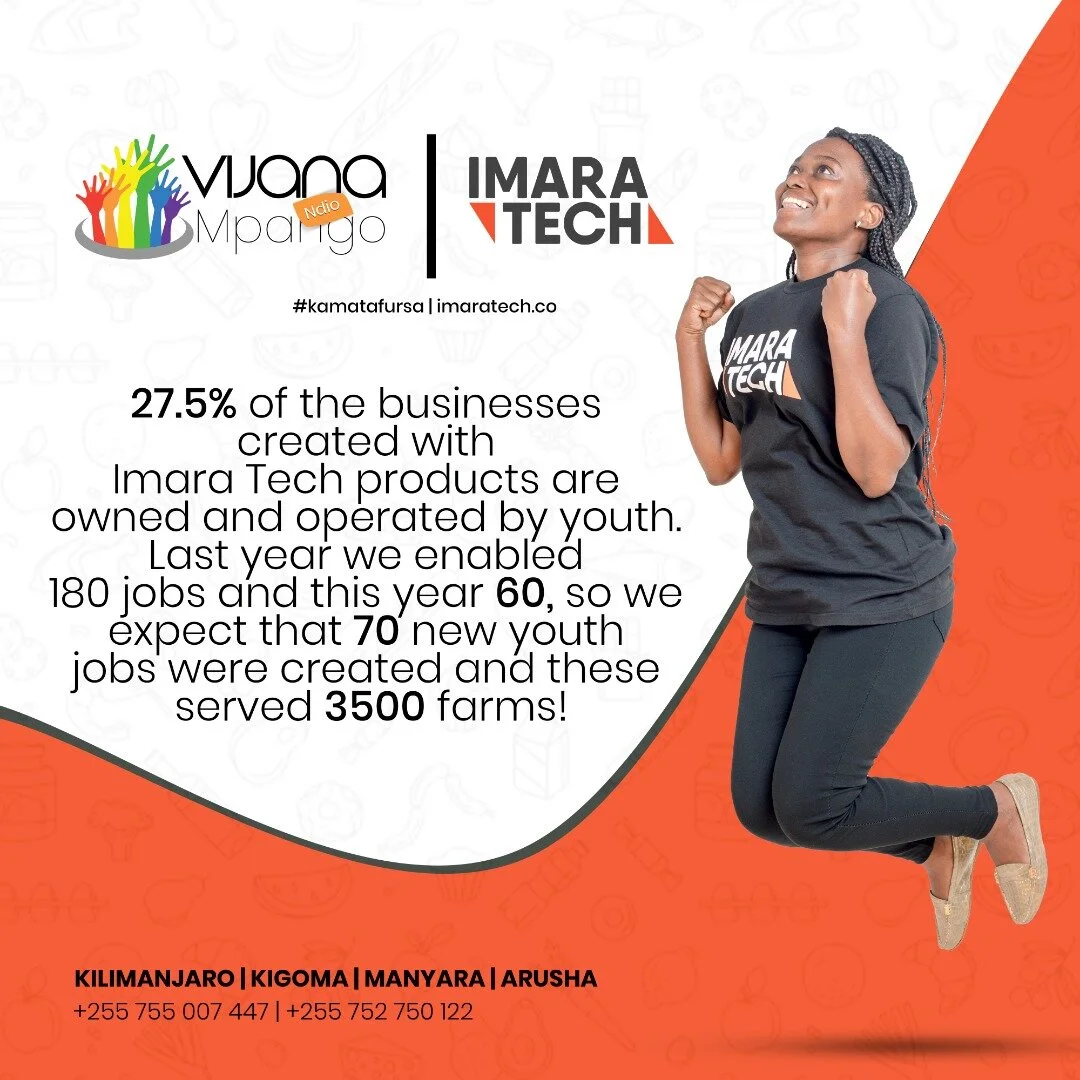

With mechanization, agriculture can be sexy, a job that young people aspire to work and see a future in. Last year, Imara Tech products enabled 50 young people to start jobs selling mechanized services to an estimated 2500 farmers (2).

There’s 6M small farms in Tanzania and little mechanization – it’s a blue ocean market, ready for young entrepreneurs to venture into.

Sources

Wineman et al, The changing face of agriculture in Tanzania: Indicators of transformation, Development Policy Review, 2020.

Imara Tech Customer Impact Survey 2020

Day 4: Models for Youth Employment in Agriculture

13 months ago, we met 24-year-old Rashid (name changed for privacy). Rashid comes from a rural village, has a wife and two kids, has a middle school education, and worked as a middleman buying and selling crops from farms.

Rashid bought an Imara Tech thresher on financing to start his own crop threshing business. He paid a down payment of 1M TZS ($435) and took on a 3-month term loan to pay off his 660k ($300) loan balance.

We tracked Rashid’s income and operations and within the first month of purchasing his machine, he had earned 1.54M TZS ($670) by selling threshing services to 130 farms. That month, he threshed over 100 tons of grain, saved his clients 76,000 hours of manual labor, and paid off his loan balance.

13 months later, Rashid’s primary form of income is his threshing business. He’s earned an estimated $1600 and used the income to buy a cow, a farm, and a plot of land to build his house. He’s not only providing for his family and empowering his community: he is increasing his family’s resilience by diversifying his income.

Rashid’s story is inspiring, but when people have access to productive-use equipment then it’s not uncommon. Our 2020 customer impact survey found that our thresher customers serve an average of 50 farms each season and earn an estimated $750, enough to recoup their investment in the machine.

Scaling threshing technologies creates jobs, reduces post-harvest losses, and improves the productivity of communities. But why stop at just threshers? What if we mechanized all of agriculture across small farms?

To hear Rashid’s testimonial in Swahili, visit our Instagram. An English subtitled version will be shared soon.

Day 5: A Portfolio of Productive-Use

An entrepreneur that’s earned their income from a thresher has unlocked capital to invest into new businesses. While that may be cows or land, it could also be other equipment that complements their existing businesses.

Planting is one of the most labor-intensive tasks on a small farm and small farms are often limited by how much land they can manage on their own. Mechanized planting offers an opportunity to reduce labor, increase the area farmed, and increase yields by offering more control over seed spacing, planting depth, and soil disturbance.

Smallholder farmers in Tanzania pay up to $9 per acre for improved planting services. Last year, we helped fabricate oxen-pulled conservation rippers with ECHO East Africa that can plant half an acre per hour. Now, we are prototyping a mechanized version that could be used for a planting business that could be run and operated in the same model as the thresher: an entrepreneur who purchases the product can sell planting services to farmers in the community, earning income for themselves and boosting the productivity of the customers.

For pastoralists or farmers that raise livestock, shredding organic matter is important for improving the nutrient uptake and digestibility of animal feed. For these users, we have made a chaff cutting machine that can grind maize cobs and shred straw and grass. Using it as a service, users can cut maize stalks from an acre of land in one hour, earning themselves an estimated $20 and providing enough feed for a farmer to feed 4 cows for a month.

While for some businesses it’s important to have a portable power source, others can be stationary, and for these there are opportunities to use solar and wind power to run the equipment. We have been prototyping and piloting solar-powered agricultural machines: flour mills, oil presses, and peanut shelling machines.

Running high-powered equipment with solar can present technical challenges, but when done right the impact can be profound. In one of our solar oil press pilot locations, three farmer groups representing 173 farms produce a combined 1M avocadoes each year. If pressed into oil, their crops can net an estimated $86,000 annually.

A solar oil press site. Farmers in this area produce 1M avocados each year. For more on this work, check out the write-up put out by A2EI.

The concept of productive-use isn’t limited to just service businesses. Irrigation technologies are often used on a single farm to enable the owner to grow higher-value crops such as vegetables. In some cases, irrigation enables farms to harvest more than once per year, creating multiplicative effects on their income.

These kinds of technologies create opportunities for income-generation and have the potential to transform even the smallest of farms into a livelihood that young people are excited about. But often, the technology is just one part of the equation; realizing the impact of productive-use at scale will require more.

Day 6: Scaling Productive-Use Employment

Three years ago, Imara Tech launched its first workshop and started marketing and selling threshers to the public. Since then, we’ve pitched our products to thousands of people across multiple regions of Tanzania. Our products have enabled hundreds of new agribusinesses to start and enable mechanization to tens of thousands of farmers.

From this experience, we’ve gained insights into what our customers need to successfully start their own agribusinesses and how we might empower others.

Awareness

The first thing that is needed to make productive-use work is awareness, not just of specific machinery or products but of the opportunity to start a business with a product. On the ground and in the field, messaging needs to focus on the business potential rather than the product. More broadly, we need to reframe how we understand and speak about small-scale agriculture: painting smallholder farming as a job for poor people only serves to discourage investment in its development. Poverty narratives blind us to the reality that this sector currently provides for millions of households and that there are many impact and business opportunities in developing it further. It’s time we stop talking about poverty and start talking about opportunity.

Reduced Financial Barriers

While our experience with cash sales has shown that there are customers able to invest in productive-use businesses, young people don’t typically have the financial capacity to do so. Whether through asset financing, micro-finance, PAYG, end-user or supplier subsidies, or other models, a reduction of financial barriers would help to accelerate the scaling of productive-use livelihoods like throwing gasoline on a fire. It’s commonly accepted that young people need financial aid to attend university or trade schools and develop their skills for employment. In an overcrowded job market, we need to revisit this idea: if most youth will employ themselves, then the financial assistance they require needs to be expanded to include their business start-up costs.

Training

Once someone has understood the business proposition and is financially able to invest, they still need training on how to use their equipment and make their business work. In our sales model, customers receive basic training on equipment operation from the sales person (either sales staff or commission-based agent) when they buy their machine, as well as a physical user manual and several video training manuals. Our experience shows that this is not sufficient and that most of our customers require an in-person, practical training for their businesses to succeed.

Products

Last but not least, we need the right products. Productive-use often sits at the awkward overlap of sectors such as agriculture, energy, and development, which each bring their own biases to the topic. At its core, productive-use is about employment and economy and this needs to be maintained as the true north. For our own products, we say this: we enabled over ten thousand farms to access mechanization last year not by having the cleanest grain thresher or the most affordable products, but by providing our customers a fantastic return on their investments.

Day 7: Vijana Ndio Mpango, Youth are the Future - What’s Next?

Since the start of our Vijana Ndio Mpango campaign, we’ve conducted marketing campaigns at markets across northern Tanzania, broadcasted our messages over radio and television, reached hundreds of thousands of people online, and shared our stories with our international support network to raise awareness about challenges facing youth and how we can address them.

Through our dialogues on this topic, we’ve revisited how we engage with youth and how we can support them further.

In the coming weeks, Imara Tech will be launching the Imara Tech Academy, a program to empower youth to start new agribusinesses and employ themselves.

Students will pay a low-cost fee to enroll themselves in the Academy programs that provide them a productive-use asset and the appropriate financial, business, and practical training to start and manage their new businesses. The income they earn from their businesses will enable them to pay back the cost of their equipment and graduate as self-sufficient entrepreneurs.

The Academy programs will span the productive-use space, from threshing businesses to off-grid milling businesses to irrigation-enabled tomato growing businesses, and be offered directly to the public as well as through partner organizations.

Hundreds of thousands of young people enter the labor market every year and find there is no place for them. Through this program, we hope to give the younger generations the opportunity to build their own businesses and thrive.

This concludes our #VijanaNdioMpango campaign. Over the coming weeks, we will compile photos, videos, and statistics from our on-the-ground activities and summarize and share these.